ORIGIN AND MEANING

ORIGIN AND MEANING OF THE FAMILY NAMES: BOOTH AND SCRIPPS

Generally speaking most English Surnames are derived from place or trade names as a way to further identify a person with a given first name. The exceptions are aristocratic surnames which often identified manly attributes or deeds, eg. Lion Heart, Mortimer (fear death), Buccleuch (the man who saved the King of Scotland by killing the huge Buck that attacked him in the Leuch or valley). etc.

A fourth form of surname identified a person as the son of another. FitzGerald is a combination of the French word for son “fils” translates as “fitz” in Norman French, and the name of a knight (actually a close companion of William Duke of Normandy). The son of the knight Gerald becomes FitzGerald. Similarly Anderson is literally Ander’s son.

Another variation on a place name could be the mixing of a place name with an aristocratic name. For example the Knight Gilbert might have others serving in his household who would be identified with him as Sir Gilbert’s man or simply a given name followed by his employer, Gilbert , eg. Dan Gilbert. Or the place name might refer to the local lord, ie. Sir Hugh’s Town becomes “Houston”.

Place names can also be descriptive. One example is the family name Windsor, obviously named for the town and castle of Windsor. But the town and castle refer to a place, a major ford or length of very shallow river allowing a important crossing of the River Thames where the river winds just west of the castle. So Windsor means “winds” + “ford”= Windsor.

BOOTH … a place name

A “booth” was a temporary stall for purposes of trading. It’s thought to be old Norse for a temporary shelter or dwelling and passed into usage in Middle English.

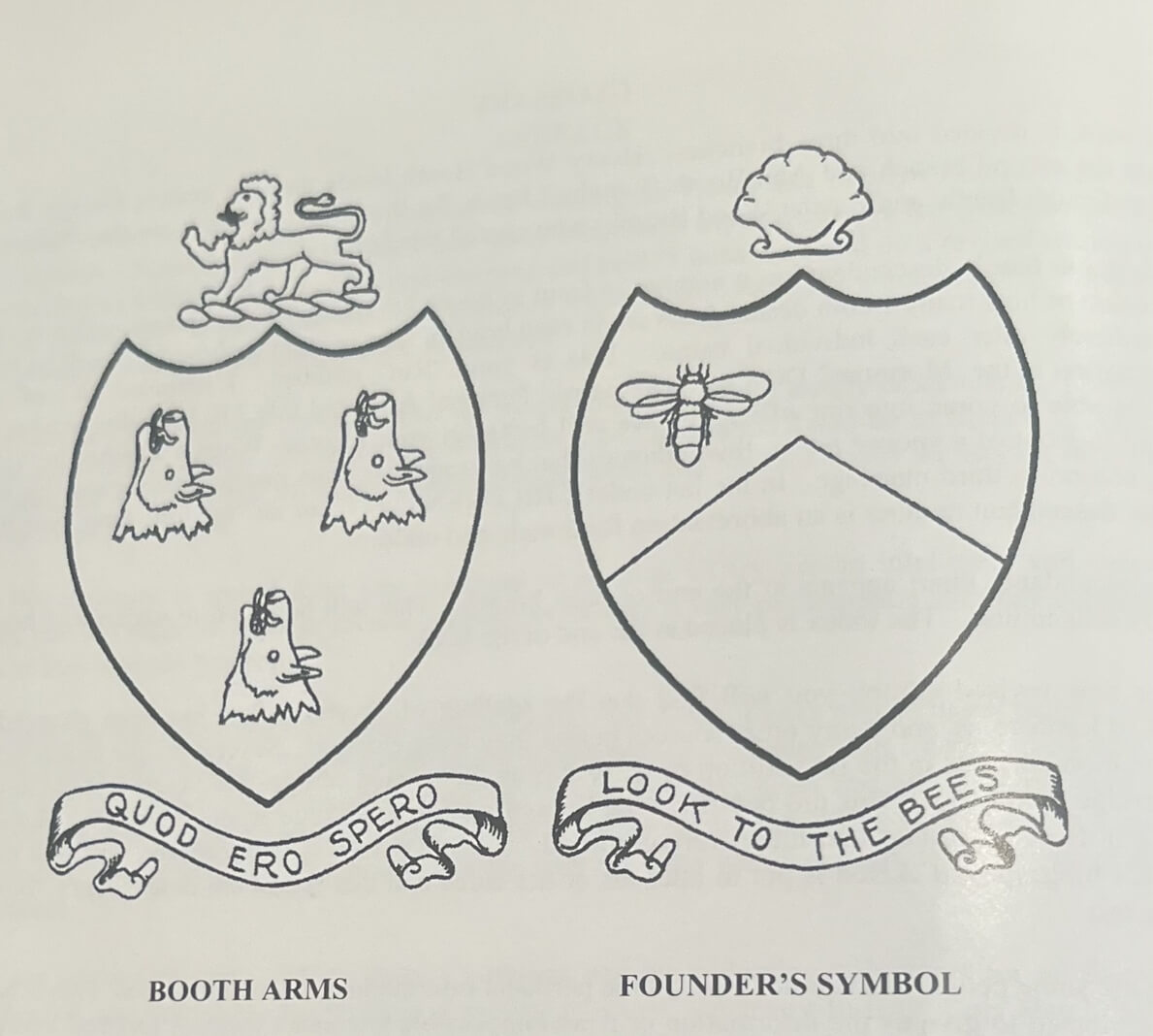

THE BOOTH aristocratic family from which we take the coat of arms of the Shield: three boar’s heads inverted with flanking SUPPORTERS: two Boars rampant and a CREST: a Lion rampant, with the family motto “QUOD ERO SPERO” (Latin translation: “I hope that I shall be” or “I shall be what I hope to be”…translated with the Latin verb Esse understood) were seated in northern England in the County of Cheshire just west of Manchester. The story of this family is illustrative.

Boothby was a medieval village located approximately 20 miles west of Manchester. In the middle ages the village was the site of a major wool fair, hence the folk living near the fairgrounds were said to live “By the Booths” , or simply Boothby. The villagers would have been referred to as Booths or Boothbys. Over time one amongst this group was elevated to the hereditary rank of Baron. This family built their family seat or baronial hall on top of a nearby large hill upon which originally stood a fort or tower and a small village which were cleared away. In French such a hill was known as a massif and in Norman French a “massey”. In old Scottish gaelic, a fort was known as a “Dun” and in old English a village was a “Ham”. Ergo, the Barons Booth named their family seat Dunham Massey. This house was greatly expanded in the eighteenth century and is now a major Cheshire National Trust Estate.

While there are other locations throughout England that share the Booth place name, this location is in the heart of the metalsmithing craft area, which is famous for making steel and copper, eg. Wlkinson Sword of Sheffield and Leeds. Furthermore its early date suggests a probable early, if indeed not first, use of the name “Booth”.

The other features of this region of Cheshire include the important, still preserved and ancient, forest of Delamer, which lies just west of Dunham Massey, and on the other, western side of the forest … the town of Warrington. The Barons Booth held the title of Barons Delamer. This title passed down in the Booth family for a number of generations until the English Civil War. The Booths, as significant leaders in Cheshire, led the resistance against the Royalist in the early years of the civil war when Cromwell came to power, but they changed sides to support the restoration of the monarchy following the death of the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. In fact Baron Delamer led what became known as Booth’s Rebellion in Cheshire, a rising that was planned as part of a nation wide rising in support of the restoration that unfortunately for Baron Booth was cancelled at the eleventh hour resulting in Baron Delamere’s capture, arrest and incarceration in the Tower of London to await trial and certain execution. Fortune and fate smiled, however, on the Booths when Charles II was shortly therafter welcomed home by Cromwell’s turncoat generals. For his demonstrated loyalty to Charles II, Henry Booth, Baron Delamer, was elevated to the new Earldom of Warrington and was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. Henry Booth was now a “made” man. His son George Booth, became the second Earl of Warrington in 1675 and lived to 1758. George married Mary Oldbury, the daughter of an immensely rich London merchant and proceeded to not only expand and improve Dunham Massey but to amass one of the greatest collections of silver plate of the age, becoming a major patron of the major French huguenot London silversmiths and emblazoning virtually all of his silver with the three boars head shield and coat of arms. (Much of this silver survives today scattered throughout museums and private collections. It also frequently reappears at public auction.)

NOTE: The choice of boars for Booth family heraldry makes sense because of Dunham Massey’s location next to the ancient Delamer forest, which no doubt once sheltered a large boar population.

Fast forward: George and Mary Booth had only one child, a daughter, also named Mary, who married into the Grey family , Earls of Stamford, becoming Mary Countess of Stamford. Upon the death of George Booth the earldom of Warrington became vacant with the Barony of Delamer passing to a younger cousin Nathaniel Booth. Thereafter, the titles of Baron Delamer and the resurrected title of Earl of Warrington passed to George Henry Grey, Fifth Earl of Stamford, and descendant of Mary Booth, Countess of Stamford.

Coincidence?: The given names of Henry, George, and Nathaniel, as well as John used so often within the Warrington Booth family also appear frequently in the Cranbrook Booth family.

SCRIPPS….. a trade name

Having read several origin stories regarding the family name Scripps written by members of the Scripps family which speculate on the name having been possibly derived from the family name Cripps based largely on associations and ancestors from the eighteenth century, I have come to believe that both the name Cripps and the name Scripps are versions of the same family name with both referring to an ancient and medieval trade.

It is well documented in the Scripps family publications that the Scripps family origin in England was Ely, Cambridgeshire. Indeed the symbol of Ely, the great Cathedral of Ely, is a symbol used frequently within the Scripps family and is even carved into stone at Moulton Manor, the estate of William E. Scripps. Ely has always been a small island town centered on its great cathedral. The business of Ely was the cathedral. But Ely was also something else. The three wealthiest English Bishoprics in the middle ages were: Norwich, Ely and Lincoln. Why…wool! These three bishoprics had huge annual incomes from the wool trade, England’s most important export in the Middle Ages. Furthermore, all three bishops used this income and wealth to create and maintain some of the largest libraries in England and indeed Europe. They were rivals of such great bishopric libraries as Chartres in France. To maintain and expand these libraries each bishopric maintained a large scriptorium. Furthermore, since virtually the entire town worked one way or other for the bishopric, the towns folks’ names would have been entered in the church registry by given name followed by their trade. If members of a family worked in the scriptorium, their names would have been entered as follows with an abbreviation of their chosen trade as follows:

James……… scrip’s (or script’s)

Edward…… ditto

Henry………ditto

Since an apostrophe in English is used to indicate a missing letter , “Scrip’s” translates to, guess what…. Scrip(P)s… BINGO!

Even more interesting is what James Edmund Scripps chose for his first major collection: first edition books printed by William Caxton, whom history regards as the first person to bring the technology of Gutenberg’s printing press to England in 1475/ 1476, causing the redundancy of the profession of scriptor.